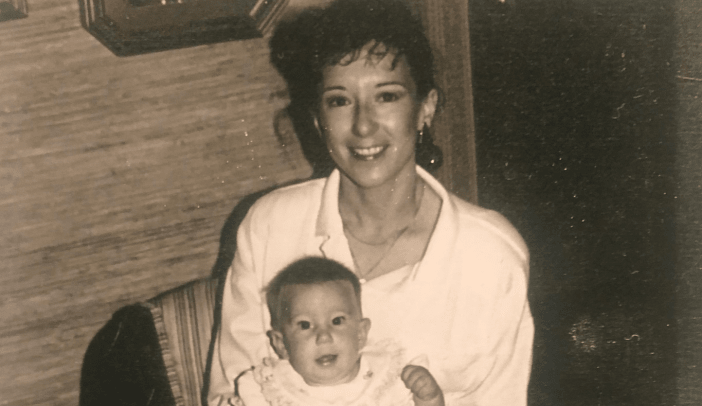

DE&I Story Sharing Series "Missing Mom – Why We Need to Consider Grief and Single Parents in DEI"

October is Breast Cancer Awareness month, a month I love and hate all the same. On the one hand, there are bountiful events (walks, fundraisers, charities) raising funds for research to help prevent and cure breast cancer. In fact, I have spent many years participating. According to the American Cancer Society, breast cancer is responsible for about “30% (or 1 in 3) of all new female cancers each year, and 43,700 women will die from breast cancer in 2023.” October is a testament to the hard work towards progress and promotes dedicated awareness, but for me October is a reminder of why I don’t have a mother.

It is 1998. I can see the red sparkly nail polish I’d painted on her toes months before as she lay exhausted from her chemo. A dream catcher we’d hung above the bed serves as a small hope that by inducing good dreams we might chase away the bad. The white walls of the hospital room cave in on me. I can hear the constant sound of regular beeps of the machines keeping her alive. There is an air mattress on the floor of the hospital where we’ve been sleeping. Boxes and boxes of Kleenexes. The doctor saying, “she likely won’t wake up”.

These are memories from when I was 9 years old and it’s mostly a blur. It all happened so fast. She got sick in November and was gone by February. It’s been 25 years since my mom died from breast cancer and it’s still hard for me to say those words out loud. Just like that I was forced into the “dead parents club”, a club no one willingly joins.

Until recently, I never thought about losing my mom from a DEI perspective and didn’t realize how often it made me feel left out or that I didn’t belong. I’ve felt alone, misunderstood, and lost, and have gotten great at pretending to be okay and “normal”. I always knew my childhood was different, especially as a young girl growing up without a female role model. The more exciting things for other girls my age became overwhelming fears, brought discomfort and embarrassment, or were simply triggering… how would I shop for specific things I needed as a female with a single dad? Who would teach me to do hair and makeup, and help me through the awkward phases of middle school and high school? Dare I say that shopping for new clothes was not fun? Don’t even get me started with dating. This would continue throughout my life and each time I would feel my trauma and loss all over again. I always take on the burden of making sure people don’t feel uncomfortable when they ask where my mom is, what she does, where she lives. How many times have I stifled my anger when people complain about their mothers when I only wish I had more time with mine? Will I ever stop cringing when the doctors forget to read my chart and I have to remind them annually that my mother died of breast cancer? Am I doomed to get breast cancer? I am a professional at mammograms already and only 35 years old. Waiting on results provokes anxiety in me every time. Will I ever not hate Mother’s Day? A joyous holiday for so many others creates a feeling of absence, and does not feel like a cause for celebration. Even now, things other women cherish sharing with their mothers – weddings, pregnancies, grandma duties – I will never experience. I watched my mom lose a lot of what made her feel like a woman, and she never got to see me turn into one.

I have spent much of my life knowing I was lacking something others have, not only a mom but a two-parent household. The older I get, the more I realize how challenging this must have been for my dad and how we had to evolve as a family unit because we were different. Here’s some examples:

We experienced grief early in life and our friends could not relate or understand.

My brother and I were forced to take on more responsibilities and grow up faster than most kids.

I started therapy sooner than most, which comes along with a fun stigma itself.

Lots more planning required for schedules and to get us from one place to the next (how do single parents travel or have an uninterrupted work day, make it to after-hours events, etc.?) To my dad’s credit, we never missed out on after school activities, even if that meant buying multiple tutus, attending dance recitals, and being the only dad in the room amongst the dance moms.

We lacked the benefit of having two people cover the roles of breadwinner a caretaker, and one income stream supporting the family.

We had to get comfortable being uncomfortable, especially having to explain why our mom isn’t here and reliving the trauma each conversation.

A feeling of being left out or not belonging (mother/daughter specific experiences or holidays)

A stronger fear of abandonment and of losing the people you love. The loss of a parent disrupts our foundation – our very sense of security and safety. For younger children, grief often gives cause for worry and manifests into anxiety, which is something I struggle with to this day.

I don’t know how my dad managed it all, and as an adult can now see the toll it had on his work-life balance in comparison to other parents. Recent research from the campaign group Single Parent Rights, highlighted that “up to 80% of single parents have faced discrimination – from stigma and negative stereotyping to exclusion from government policies.” Now more than ever, single parents need to be included in diversity and inclusion strategies, but unfortunately very few institutions consider addressing the entrenched stereotypes and bias towards single parent families. They are often the forgotten and invisible group in DEI strategies. My dad was dealing with a double whammy, challenges as a single parent and his own grief from losing his partner.

At this point, recent years and events have likely left all of us with an unprecedented amount of loss. The truth is, grief is a universal human experience and something that can bring us together. The problem is, that as a culture we don’t know how to deal with death. It’s uncomfortable. And when we try, people often reach for prepackaged sentiments without giving much thought as to how these responses further alienate and isolate the grieving person. Bereavement and loss can trigger feelings of profound marginalization, and we need to create a more inclusive culture for those who are grieving. Losing someone you love is a life-altering experience that can make someone feel different from their peers. In turn, feeling socially isolated can hurt self-esteem, and ultimately put people at risk for anxiety, depression and substance abuse if not addressed in healthy ways.

So, we must ask, are we intentionally holding space in a way that supports grief in the workplace and beyond? Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts must consider helping those who have experienced grief and loss to be seen, understood, and valued, and to have the support and resources they need to do well and thrive in their lives. It is important to point out that marginalized communities experience grief at a much higher rate, which is often compounded by other factors impacting these groups. And let’s not forget about the single parents. While our understanding of family is evolving, there is still work to be done. The nuclear family in the U.S. has changed. Consequently, so should our thoughts and our words so that we don’t behave in ways that are exclusionary.

In many ways our grief intersects with our identity. Though I experience a range of emotions about the loss of my mother, I also know that my grief is a part of me and has opened me to a depth of experience I would never have known possible. It is an incredible burden and an incredible gift that not everyone can understand. I am who I am today because of it – strong, independent, responsible, resourceful, helpful, empathetic, and resilient. I learned at a young age that I can have really challenging things happen in my life and I am able to deal with them. We don’t get to choose the hands we are dealt, our backgrounds, what we are born into, or our experiences; however, we can choose how we move through the world and make it a better place because of what we’ve been through and by embracing who it made us to be. I’m really proud of how I grew without her, but I really wish she could see where I am now.

I owe you everything, Dad. I miss you, Mom.

CREW Denver DE&I Mission Statement

Nominate Someone to Share Their Story